Classifying Subtypes of Aging Cells

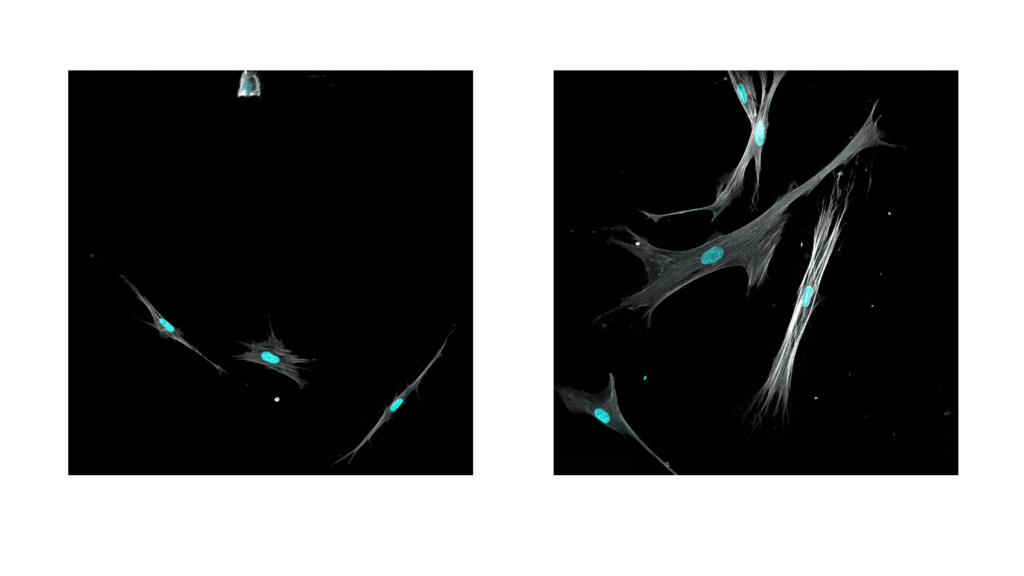

Above image: Microscopy images of dermal fibroblasts from a 23-year-old donor. The cells on the left are healthy while the ones on the right are induced senescent cells. Photo credit: Pratik Kamat.

Jude Phillip, core researcher at the Institute for NanoBioTechnology and assistant professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering has received a Junior Faculty award from the American Federation for Aging Research—Glenn Foundation to identify and classify subtypes of senescent cells. Senescence is a biological process that causes cells to stop replicating and is believed to contribute to age-associated illnesses.

Although older adults tend to have more senescent cells, senescence cells can accumulate at any point in a person’s life. The process plays a beneficial role in some situations, such as wound healing and embryonic development. However, in others, it can be harmful because the cells exhibit behaviors, such as inflammation and tumor formation, that can cause diseases. Researchers think when senescent cells accumulate, as is the case in older adults, that the cells can have compounding and damaging long-term health effects.

The field currently views senescence as binary, that is the cells are either senescent or not. Phillip and his team think that when a cell becomes senescent, it is much more complex than flipping a switch from an off to an on position. Rather they, think there is a process with the cells experiencing variations, or subtypes. When cells are in different states of the senescent process, they will exhibit distinct characteristics and behaviors. Not only that, but the subtypes could also differ based on several factors, including a person’s age, assigned sex at birth, ethnicity, lifestyle choices, and more.

The team started thinking about senescent subtypes after reading recent literature on the context-dependence of senescence and the mixed results from clinical trials for drugs that aim to kill senescent cells, known as senolytics. In some cases, it’s beneficial to have senescent cells around and in other cases it seems to be bad. This context-dependence lead them to think that there are distinct subtypes, and that these subtypes may be functional, meaning that they can drive different biological responses. These responses could be based on what molecules they secrete, how they modify their local microenvironments, or even how they communicate with neighboring cells.

“We are extremely excited to receive this award and we think that the eventual findings could offer new ways to think about senescence and aging. I think that if we can identify the populations of senescent cells that are “bad”, and target only those, we should eventually be able to translate these approaches to impact the aging and health in older adults,” said Phillip.

Latest Posts

-

Year in Review 2025

January 5, 2026

Year in Review 2025

January 5, 2026

-

Cellular building blocks may enable new understanding of the body’s “machinery”

December 19, 2025

Cellular building blocks may enable new understanding of the body’s “machinery”

December 19, 2025

-

Biomedical Engineer Jamie Spangler Receives President’s Frontier Award

December 15, 2025

Biomedical Engineer Jamie Spangler Receives President’s Frontier Award

December 15, 2025